No Ficken Joke

Sterling Opera House, Derby

I suppose I could have tried to get a personal tour of this place. After all, NBC30 did. So did Atlas Obscura as well as Damned Connecticut. In a way, I consider all three of those outlets peers. I’ll also consider them primary source material for this page. Because, as you’ve gathered, I did not get inside the long-abandoned Sterling Opera House.

Yes. Tiny Derby had an opera house that sounds like it belongs way east in Sterling. There are a lot of questions surrounding this joint, and I think I have the answers. First, no, it is not haunted. There are no such things as ghosts. Cool? Cool. Let’s move on.

Why does Derby even have a stately theater? After all, New Haven is right next door and has a bunch of stately theaters. Moreover, Ansonia – which is even closer and used to be part of Derby – also has an opera house. What’s up?

Turns out a bunch of towns all around the country got opera houses in the late 1800’s. It was a thing. And since Derby is at the confluence of two majorish rivers (the Housatonic and Naugatuck), there was a good amount of industry here. That meant people. People meant patrons. Thus, a stately theater.

One of those local businesses was the Sterling Piano Company. The Sterling Opera House was named for Charles A. Sterling, the founder of that company. So Derby was plugging along and the next thing the fine people there knew, Ansonia up the road built an opera house. (It it also still standing and abandoned in 2023.) Fewer people lived in Ansonia than Derby at the time, and the people of Derby were rightfully sore about the situation.

Derby went all in. The plucky little town hired the prestigious architect Henry Edwards Ficken, one of the creators of Manhattan’s illustrious Carnegie Hall, and the architect of Coney Island’s steel pier and the Bronx’s Woodlawn Cemetery. Ficken also went all in. He designed the building in the Baroque Italianate style, complete with striking terra cotta exteriors and a stained glass cupola towering over the small town’s square. The building is so striking it was the first building in all of Connecticut to be added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1968.

Whoa. Is that true?

Yes, that’s totally true. Wikipedia says so: The building was constructed in 1889 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 8, 1968, making it the first building in Connecticut to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The cool thing about this building is that even in 1889, it wasn’t just a theater.

The Sterling Opera House served multiple municipal purposes as a city hall and police station when it opened. So it was a purpose built multifunction building. And after the theater closed in 1945, the city continued to use the building as a city hall and police station for 20 more years. Wait, so the “opera house” part of this place has been closed since WWII?

Yes. And people think it’s going to be revived somehow in 2023? I think so. The last time anyone mentioned any money towards doing so that I can find was in 2011, and the amount was a pittance. The entire place is woefully out of code and falling apart inside. But they did make the outside look great, I’ll give them that.

Somehow, the Sterling attracted many world-famous performers such as Harry Houdini and Red Skelton back in the day. In addition, George Burns, Gracie Allen, Milton Berle, Bob Hope, and Bing Crosby were among the many other stars that graced the stage here. Hm. Those four together actually sounds like a one-night show where all those people showed up once. Regardless, we’re talking about Derby here, so that’s still impressive.

And since we’re talking about Derby, I must mention this tidbit: D.W. Griffith, the talented but racist silent filmmaker, chose to premiere many of his film productions at the Sterling after a delightful reception to his film, Birth of a Nation. We can’t really impugn the fine people of Derby, but that film, with its overtly pro-Confederate sympathies and racist overtones, was banned in several major cities. Riots broke out in Boston and Philadelphia when the film was shown, while Chicago, Denver, Kansas City, Missouri, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh and St Louis all refused to show it. You do you, early 20th-century Derby.

And hey, guess what else happened right after the Sterling opened? Ansonia seceded (sort of) and was incorporated as its own city. There’s an apocryphal story that when the Sterling opened with a play called “Drifting Apart,” that Ansonia took it as an affront. It was ridiculous that Derby built this thing in the first place, but now they were putting on plays with not-so-subtle references to the Ansonia vs. Derby split. Supposedly, the opening of the Sterling was the final straw for Ansonia and the town split off as soon as they could afterwards.

I think Derby vs. Ansonia high schools are still heated rivals to this day.

The Sterling itself is a pretty bonkers venue. The theater featured a large auditorium with a striking proscenium arch framing the stage. The seating arrangement was influenced by German Composer Richard Wagner, whose conception of a triangular layout enabled all theatergoers to enjoy unobstructed views of the stage. Its acoustics rivaled those of New York City’s Metropolitan Opera House; even a whisper could be heard at the back of the theater. But the upper balconies are impossibly steep. And it only seats maybe 1,200 on a good day.

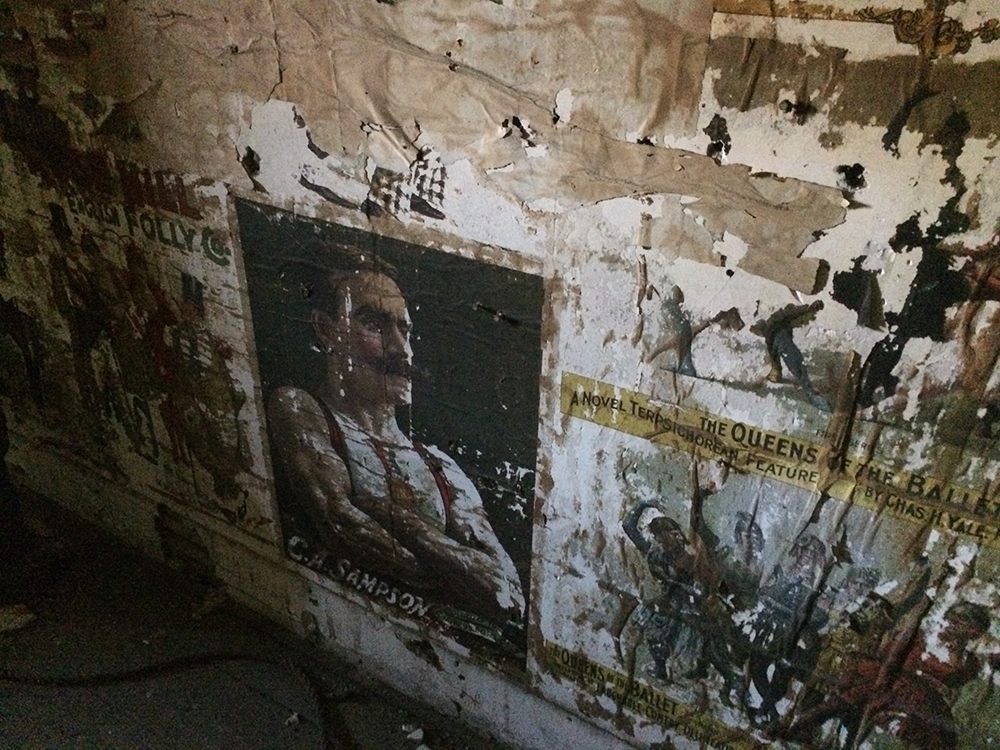

Photo from Damned Connecticut

Again, if I wasn’t clear, I have not been inside the building. Heck, I barely got out of my car to take pictures of it. But Luke Spencer from Atlas Obscura did, and here are some choice excerpts of what he saw. (Pictures below also from Atlas Obscura).

Walking into the abandoned opera house today, the interior is a striking as the Florentine exterior is beautiful. A ground floor and two sweeping balconies, decorated with intricate wrought iron work, slope down to the old orchestra pit, with the 60-foot stage framed by a grand proscenium archway. The interior has remained surprisingly pristine in the cool dry air, just covered in a layer of dust that has gathered since the local fire marshal closed the doors for good in 1945.

Artifacts of the building’s heyday can still be found beneath the dust. The seats on the ground floor have all been removed, many lying under tarpaulins to the side, but the wooden seats on the two balconies still remain. Flipping up the wooden seats you can see the original wire racks underneath the seat, where gentlemen could store their hats for the evening’s performance. Two seats hold a particular secret, a peculiar stenciled star within in a circle that is thought to have been where a prize would be given out to the person sitting in the lucky seat. Some of the old background scenes, one depicting an enchanted forest and another a view of a seashore, rest on the stage. Over 100 years old, these would have been used as backdrops in long forgotten plays. On either side of the stage are two piano boxes, designed to hold Sterling pianos, one of which is still there and in fine condition.

Immediately underneath the stage are a series of old dressing rooms. The walls still bear ghostly reminders of past performers thanks to old posters pasted to the wall. Names of old vaudeville performers such as Sampson the Strongman, or “Zelda the Snake, the World’s Greatest Contortionist”, are forgotten to history but were once amongst the countless other performers who toured the country.

One particular dressing room has something even more remarkable. Used by the dancing girls of the chorus line, some of whom left their own mark on the abandoned opera house by kissing the walls and leaving the imprint of their lipstick.

Incredibly, despite being nearly a hundred years ago, the bright pink kisses still remain on the wall.

There is something underneath the street, though, that sets this opera house apart.

Underneath the stage, with no sunlight, are a series of empty rooms and corridors. Peeling teal paint covers the doors, the glass windows stenciled with gold names such as “Mayors Office”, “Alderman” and “Deputy Commissioner of Charities.” The Sterling Opera House was built not only as a palace of entertainment, but also as the local civic center.

Despite the last staged performance occurring in the winter of 1945, the leaders of Derby used these offices for another 20 years.

The seamier side of public life was also part of the opera house basement—namely, city prisons and the police department. The row of jail cells sit in disrepair but the sliding doors still slam shut, echoing eerily throughout the abandoned opera house. Amongst those who were locked up here included captured members of the violent Italian organization La Mano Nera, or the Black Hand. It is quite likely that those incarcerated in the subterranean dungeon would have been able to hear the singing and sounds of the orchestra performing high above their heads.

According to my volunteer guide, this eerie subterranean prison once briefly held Lydia Sherman, one of the America’s most notorious female serial killers. Known as the Poison Fiend, Sherman was the archetypal Victorian “black widows,” murdering 10 victims with arsenic, including three husbands and seven children, the youngest just 9 months old.

Intense. Though it was designed by Henry Edwards Ficken, the Sterling Opera House is no Ficken joke.

![]()

CTMQ’s Houses, Ruins, Communities & Urban Legends

Atlas Obscura and Damned Connecticut articles

Stuart says

Stuart says

January 27, 2023 at 1:44 pmI saw the Carl Palmer Band at the Broad Brook Opera House in East Windsor recently. Build in 1892, it has been refurbished in 2018. Fits in with the timeline you wrote.

https://broadbrookoperahouse.com/

Paul says

Paul says

October 27, 2024 at 10:30 amThere is a current committee endorsed by the mayor. The goal is to see the Opera House restored. It does have traction and plans are underway albeit slowly, but there is a plan.